Cornelius Stahlblau is a writer whom I’ve struck up a friendship with via Twitter and through Justin Murphy‘s Indie Thinkers group. He authors The Outpost, a substack blog devoted to organic prophecies, esoteric analysis and wild speculation on things you didn’t even know were happening.

Cornelius Stahlblau is a writer whom I’ve struck up a friendship with via Twitter and through Justin Murphy‘s Indie Thinkers group. He authors The Outpost, a substack blog devoted to organic prophecies, esoteric analysis and wild speculation on things you didn’t even know were happening.

To get acquainted with The Outpost‘s style, I would first point readers to a piece about Kazakhstan, Ukraine, and oil interests in the Russian Near Abroad. The following excerpt riffs on the artful weirdness of Kazakhstan, which is a major fossil-fuel exporter that produces more than 40% of the world’s uranium.

…Kazakhstan is an alchemical regime, sustained both by (1) harnessing the dark chthonic power of decayed organic matter; and by (2) selling the means to break the atom, thus bending the laws of matter to Humanity’s avid will. As if this were not enough, a lot of its inner coal consumption is spent in crypto mining, producing 18% of the world’s Bitcoin hashrate. In an act of necromantic lust, Kazakhstan annihilates creatures dead eons ago into a digital simulacrum of gold.

As James Simpkin wrote on Twitter: someone get this guy a book deal.

Stahlblau is also a military doctor who was deployed in Afghanistan during the withdrawal of U.S. troops (and their allies) in the summer of 2021. He’s written for Covidian Aesthetics and appeared on Colin Plamondon‘s Honor and Profit podcast.

We recently did a longform Q&A via email. Shortly after I emailed him my questions, Russia/Ukraine became the dominant daily news story, thereby relegating the previous big news story, COVID, to temporal artifact status, and placing our interview in a strange, ambient limbo.

Q: You wrote about being in Afghanistan during the withdrawal last summer. This paragraph in particular caught my eye:

The Age of Mass Migration (1850-1950) saw unprecedented demographic movements; not only across the Atlantic: just the partition of India in 1947 caused the displacement of 18 million people, igniting the process that gifted the world with two new nuclear powers, India (1974) and Pakistan (1998). The forced population displacements carried out by the Soviet Union in its sphere of influence also transformed the demographic and political landscape of the entire region irreversibly. The chaotic, conflictive and historically aggrieved ethno-religious kaleidoscope that was Central and Eastern Europe before the Second World War—what Timothy Snyder called the Bloodlands—became the enduringly intricate, if much more intelligible, geopolitical space we know today.

This was the first time I ‘d ever heard of Snyder. Which specific areas constitute the Bloodlands? An Amazon reviewer describes this space “as the lands between pre-war Nazi Germany and the western edge of the Russian Republic, predominantly Poland, Belarus, the Baltic States and Ukraine.” But I get the sense that the term has a broader, maybe more metaphysical meaning?

A: The Bloodlands, at least to my knowledge, refers to those areas in Central and Eastern Europe that were most contested between Nazi Germany and the USSR. As such, they changed hands many times and were subject to a lot of violence, due to military and counterinsurgency operations going on. What makes them remarkable, according to Snyder, is the often enthusiastic participation of the population in this violence, and the importance of the ethnic-religious factor in its occurrence.

In fact, a lot of this territories belonged to what used to be the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, back in the 17th century. This polity was interesting in its organization, as it was more or less a nobles’ republic in its golden era, which in Polish is called Złota wolność (Golden Freedom). One of the characteristics of this political regime was a relative religious and cultural tolerance, so you had Poles, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Germans, Jews, Russians, and Muslim Tatars all living very close to one another; all of these peoples had very distinct languages, traditions and cultures, and coexisted in the area.

The Commonwealth disappeared at the end of the 18th century, partitioned between a newborn Prussia (Germany did not exist yet), Austria, and the Russian Empire. The partitions did not change much the ethnic make up of the territories, which remained very heterogenous all throughout the 19th century and up until the 2nd World War. This being an ideological conflict, the different factions sometimes supported different sides in the War, which led to collaborationism and frequent pogroms and massacres between neighbors, who had stakes on who won the war and became dominant in the region. The accusations we see nowadays of Ukrainians as filo-Nazis come precisely from this era, as they tended to favor the Germans and were used by them against Jews and Poles. In fact, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists stemmed from meetings in Berlin, Prague and Vienna, in the late 20s.

Q: On a personal level, what images and memories remain with you after the experience in Afghanistan?

A: The invasion of Afghanistan started when I was still in Elementary school, and Bin Laden was killed well into my college years, so my adolescence more or less overlaps with the war. One of the reasons I enlisted was because I wanted to be a direct witness to the dramas of my era, and being present at the dramatic finale of such an epochal conflict is an experience that I cherish dearly, as heart-wrenching as it was. It was just a few days, but when I came back I felt as if I was definitely not young anymore. Getting married immediately afterwards also helped settling this feeling for good.

The eyes and faces of the people we evacuated will stay with me for a long time. I remember a few in particular: an old lady, paralyzed by Parkinson’s disease, who after having lived 20 years of war was finally going to end her days in a refugee camp somewhere in Europe, with no knowledge of the language nor any connection to her previous life. A very strange destiny.

Seeing the exhausted, sometimes barefoot kids was also striking (we treated some because their soles had been burnt in the hot airway). One can find many things wrong about the West today, but it seemed to me that the evacuated children, of which there were a lot, were the big winners in this situation and their lot in life has generally improved.

Many of the people who came with us were fleeing VIPs, too, of course. I remember a young girl asking me for an iPhone charger, which of course I didn’t have. These people or their families were valuable collaborators, just as the humble guys who might have been interpreters or whatever more than a decade ago. One of our NCOs, who had been a private in the early days of the war, actually had the chance to hug an old acquaintance and share memories of old adventures.

In general, since we were flying every night from Dubai to Kabul and back, for more than a week, the situation quickly wore us down. It was surreal, as we were staying in a very wealthy city during the day, which we barely had time to enjoy. We spent an awful lot of time preparing the trips, and we slept mostly on the three-hour long trip to Afghanistan. Thus, we were switching constantly from misery to splendor; all of it feels almost dreamlike in hindsight. At least I can brag about having done like 7 tours in Afghanistan (even if all of them were less than 90 minutes long!).

Q: In this piece, you trace some COVID hysteria, overreach, and mismanagement to government smoking bans and diminishing risk tolerance. You write:

Everything started with the smoking ban. Decreasing tolerance for risk in general, and for health risks in particular, have led to the false pretense that life can always be preserved by applying the correct, Science™-approved measures. Doom is not doom, but “a situation” to be technically managed.

I think I agree with this assessment, but I wonder if even weirder things are going on, possibly weirder than standard-fare groupthink, clumsy reactions to emergent phenomena, or reduced risk tolerance. There’s a Philip K. Dick line that “The [Black Iron Prison] is a vast complex life form (organism) which protects itself by inducing a negative hallucination of it.”

Is it crazy to suggest that things have gotten *this* weird? Large groups of people seem incapable of noticing bad things happening directly in front of them.

A: I agree. However, it’s true that there’s a certain kind of denial that is very natural. Many firemen tell stories of people being inside buildings on fire, who still will go on with their daily lives if nobody starts immediately evacuating, activating their herd instincts. The standard reaction goes something like this: “this is happening to me -> bad things can’t happen to me -> therefore what is happening is not that bad.” We can all be victims of this.

I studied Medicine in university, and one of the bonuses I find most valuable from the Med School experience is getting forever an inkling that things can go seriously wrong at anytime, occasionally in horrible ways. We are all kind of dying already, and yet it is always sort of unexpected. I take this with a religious perspective, which of course goes well with Jesus’ words about the Apocalypse: we don’t know the day nor the hour. I believe that living without paying attention to this is somewhat blasphemous, but of course, we all do it to some degree.

I got the idea about an idyllic time “before the smoking ban” from a mysterious Twitter account and blog, now defunct, called the G Manifesto. It had all kinds of hilarious, esoteric life advice. I’m a big fan of it and wholeheartedly recommend it.

Q: Expanding on COVID, the group substack Covidian Aesthetics, where your Afghanistan piece was published, has talked about “egregoric warfare“ in the context of COVID. And in this piece, “Ghosts of the Pandemic,” a Covidian Aesthetics author describes the spectrality of COVID and “non-places”:

The non-place seeks to bypass the old places, creating instead a series of prescribed journeys and engineered trajectories that render the traveler fundamentally transparent to surveillance, market signals, and external direction. As we stand on the uncertain threshold of a radically reorganised post-COVID world (or simply one where COVID is perpetually present), the sense of the ghostly registers our sense of what Augé calls a “willed coexistence of two different worlds,” the old and the new, and our psychic unwillingness to sever ties entirely with what has gone before.

I don’t have a specific question with regard to that passage, but I’d love to hear you riff on this subject matter — the “spectrality” of COVID and how that ghostliness informs our perception of place, and the spaces around us. For the last two years, everything has seemed out of sorts, out of time — there’s an energy that’s disorienting. Before COVID, strange “liminality” was present in odd edgelands and transitory places — airport terminals at 2 a.m., parking lots, etc. But nowadays, you could make an argument that strange liminality is everywhere.

A: Totally! I’ve always been fascinated by the concept of non-spaces, ever since I read a Rem Koolhaas’ Junkspace, a few years ago. For Koolhaas, Junkspace is the heir to Architecture, which according to him has died and been replaced by it. He describes it as “product of the encounter between escalator and air conditioning, conceived in an incubator of sheetrock (all three missing from the history books). Continuity is the essence of Junkspace; it exploits any invention that enables expansion, deploys the infrastructure of seamlessness: escalator, air conditioning, sprinkler, fire shutter, hot-air curtain…It is always interior, so extensive that you rarely perceive limits; it promotes disorientation by any means (mirror, polish, echo)…”

The archetypes of Junkspace are airports and shopping malls: mega-structures alien to the organization provided by architecture. When you are at an airport terminal, you can’t really tell where you are within it, unless looking at a floor plan. Everything is connected, featureless, and indistinct; in fact, all airports and malls in the world look alike, so you can’t really tell the city in which you are, either. Travel through these junkspaces is exactly what the quote from Covidian Aesthetics describes: “prescribed journeys and engineered trajectories that render the traveler fundamentally transparent to surveillance, market signals, and external direction.”

I think the COVID regime has helped the spirit of Junkspace colonize other spaces, by virtue of their converging values: gentle coercion, sterility, universality, control…The new virus variants are announced every season in a similar way to iPhone models or Marvel movies, every new iteration supposedly a breakthrough but ultimately a bland copy of its predecessors, which now feel outdated.

The fact that masks are often worn out and shabby, is an interesting variation on this idea. Seeing them thrown away everywhere (they are an environmental catastrophe apparently), also contributes to an appearance of “used future”; a kind of junky reality, which is typical of the edgelands you describe: peripheric power plants, railtracks in the middle of nowhere…This aesthetic, to me, is reminiscent of the outdated technology of the golden era of space exploration. We all look like jaded astronauts in a terraformed foreign world.

Also, Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), of which masks are just the most basic version, is often phantasmagoric, mostly because it is a non-verbal cue for danger. There’s an implicit threat in ghost stories, even if the harm they might pose is not made explicit. People who encounter spectral beings usually come out unharmed, yet frightened by the experience. Seeing PPEs everywhere is unsettling for this reason, probably.

Q: When I first discovered your writing, I enjoyed references to places that, to me personally, are so strange, distant, and faraway as to be almost unreachable e.g., Murmansk. A while back, I tweeted my travel wish list of obscure, faraway locales (which includes Murmansk but also Darvaza, Turkmenistan and the “Gates of Hell”). Do you have a similar list of strange, faraway places that you aspire to visit?

A: Hadn’t seen your list, we share a couple of places (Murmansk and Samarkand)! There’s many trips I want to make in the future. Apart from the two you mentioned, I’ve always wanted to see Vladivostok, at the Far Eastern end of Russia; sadly, this seems unlikely to happen with the current state of affairs. The Northwestern territories are also a place I would like to visit; especially the Nootka strait in Alaska, of which I have written before.

I’m very attracted to Central Asia in general, and would love to visit, in particular, Astana/Nur-Sultan and Ulaanbaatar. The concept of a New Silk Road is very evocative to me in a poetic sense, which translates into my interest on the geopolitical aspects of this region.

Speaking of poetic trips, one of my favourite poetry books is The Narrow Road to the Deep North. It was written by Matsuo Basho, one of the greatest poets of Edo period Japan; it’s basically a travel diary of the dangerous journey he made across the Japanese interior, and I would love to emulate him and explore lesser-known areas of the country (I’ve never been there). I would also like to travel, as a pilgrim, the landmarks of the brief history of Christianity in Japan, in the 16th century. It’s a fascinating story.

Q: Back to your piece that mentions Murmansk — in that post, you provide the first analysis I’ve ever seen of the Russian north coast evolving into a “new, amphibious geopolitical character” as Arctic ice begins to melt. I find this fascinating — the idea of certain countries, e.g., Russia, embracing an extreme maritime geopolitical makeover, rather than scurrying around in desperate attempts to mitigate climate change. It seems like Russia is well-suited to take on a hyper-realist and hyper-adaptable place in the world.

What would this look like in practice? (In the piece, you contemplate whether the melting process could turn Russia into a “trading thalassocracy, a culture of merchants…”)

A: I believe that, when one wants to make predictions or contemplate future scenarios, imagination and a taste for inventive story-telling is necessary. Nobody knows the infinite variables that control the future, so it makes sense to me that what eventually happens is what makes the most sense narratively, and not necessarily what can be inferred by current material conditions.

The article you refer to is a very speculative piece (and one of my most read, I should add), so it has to be taken with a massive amount of salt. The idea that geography determines culture and international relations is almost an axiom in materialist study of geopolitics; in fact, it’s where the discipline comes from. Logically, if geography changes massively, we can expect culture and international relations to change accordingly.

If we take the predictions about climate and the environment at face value (and this may require some effort depending on where you stand), geography might change enough in the next century to have an effect on global politics. It’s strange to imagine a world in which some of today’s hubs of sea travel lose importance due to shifting conditions. Most of the world’s largest ports lay in temperate regions: Shanghai, Singapore, Hong Kong, Rotterdam, Antwerp, L.A…These places could be hit by rising sea levels, coastal erosion, and adverse weather in a way that could greatly impact their competitiveness and change the game. They are also vulnerable to other variables: we saw this happen in L.A., with great delays caused by COVID restrictions.

It’s fun to imagine Russia, which has always been idealized as a telluric power looking for a warm water seaport, becoming by chance a major maritime player, due to North Pole trade routes becoming more stable and secure than traditional ones. We are still very far away from this situation, of course, but it’s something that could happen. In the 1920s, the possibility of precision, satellite-guided airstrikes was science fiction. Eighty years later, technology had become reliable enough to turn this into a main weapon, because the aerial medium has gained a geographical character it didn’t have back then. Singapore used to be, not that long ago, a fishing town in a swamp; modern sanitation, land reclamation efforts and the right geopolitical conditions turned it into what it is today.

What would a Russian thalassocracy look like? Probably like other thalassocracies: rich, culturally sophisticated, and venal. Perhaps it would rely on fleets of unmanned or scarcely manned vessels, which would decrease some of these aspects, deeply tied to life in port cities. Isolated islands could be home to communities providing basic services. Naval operations, in any case, require a lot of supporting infrastructure, so you could expect a more densely populated coast on all sides of the Arctic Ocean: let’s not forget that Canada and Norway would also be affected by this reality. So maybe you’d end up with Murmansk becoming a big metropolis and business center, something like Toronto. Who knows?

Q: Where do you stand on the question posed in this Michael Millerman tweet, i.e.,

“Do you agree with Curtis Yarvin that the American regime can continue in its current state for another 100 years or more, or do you agree with Michael Anton that it is so shaky that even 50 years is optimistic?”

A: I have no idea. It depends on what you consider the defining elements of its current state. I think it will remain a military superpower and a technological leader of the world for quite some time. I don’t think the culture it has been exporting for the last 70 years will be the same, neither in general nor in the political sense. Some of these former values were prosperity and freedom, which I don’t think people associate with America anymore, at least not exclusively. I agree the American regime is in crisis, but crisis more often than not lead to adaptation, not extinction.

Q: The aesthetics of The Outpost are top-notch — very visually arresting — and the latest thing to catch my eye are images of Astana/Nur-Sultan (Kazakhstan), a “‘shining city,’ saturated with occult imagery of Masonic or Luciferian undertones,” further enhanced by themes of “esoteric Sun worship.” Do you have any favorite visual artists and/or photographers, and what’s your general aesthetic philosophy with regard to The Outpost?

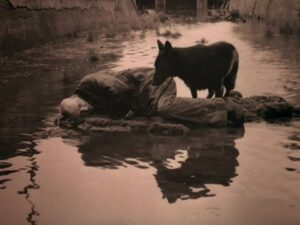

A: I dedicate a lot of time to choose the pictures I use in my articles. Although sometimes it’s obscure, there’s always a connection to the text. Although I stay loyal to reality and facts, my writing is mostly speculative; and forecasting, by necessity, often wanders into theory-fiction. I don’t know if you’re familiar with the Mirror of Galadriel, in the Lord of the Rings, which shows “things that were, and things that are, and things that yet may be. But which it is that he sees, even the wisest cannot always tell.” I think that sums up the concept of the blog, and images are a fundamental part of it.

Most of the images I use are from an extensive collection I’ve made over the years; the majority are downloaded from Twitter, so it’s difficult for me to trace the authors. After writing my articles, I browse this collection and select what I find appropriate, so often the connection between text and image is pure serendipity. I like using photos of animals, for example, as they evoke Aesop’s fables.

Getting into the specifics, an important source of pictures is the @archillect Twitter account, which I consider a fascinating experiment. According to its website, Archillect is “an AI created to discover and share stimulating visual content.” In general, that’s exactly what I look for: stimulating, striking and memorable images that tell a story or provide an atmosphere reflective of what I’m saying.

Archillect is a very cyberpunk concept, an aesthetic in which I’m very interested. I’d certainly mention sci-fi films like Blade Runner 2049, Interstellar or Tarkovsky’s Stalker. Dennis Villeneuve’s Sicario is not science-fiction, but I think does a great job in portraying how some things are done in real life.

Since the 20th century was the first of the Cybernetic Era, “primitive” references of this epoch are also important to me: I find both Italian Futurists and Russian Cosmists inspiring in this regard. Modernist and Brutalist architecture (think Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, or later Soviet works) is also stimulating, and in my writing serves as an optic byword for the cold power of the State and its technobureaucratic temples.

The 2016 documentary by Adam Curtis, Hypernormalisation, which I first saw after getting started with The Outpost, does very well what I try to do; it’s precisely about the collapse of political narratives at the end of the Cold War, and the rise of Cybernetics as the establishment’s modus operandi. The Cold War, in general, provides plenty of themes: the atomic and space races, the development of mass psychology, the pharmacologic revolution…and naturally, technology from this time reflects it, so I like pictures of power plants, rockets, planes, soldiers and office buildings.

I also like to use a lot of older artwork. The late Renaissance/early Baroque is my favorite era. Historically, it’s an age of triumphant discoveries, technical progress, deep religiosity, cultural fertility, power competition, and lots of violence. Even current photographs I use often share qualities with art from back then. I also frequently feature Spanish contemporary artist, Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau, who mostly works on military themes and with whom I share some biographical coincidences.

Q: Do you have a favorite prayer? Or any that you recommend?

A: I usually stick to the Paternoster, the Ave Maria, and the Gloria. I’m a simple man.

Q: Can you give me a few random predictions for the next decade (political or otherwise)?

A: It’s a difficult moment to predict anything, but I’ll place the following bets:

–The US will stay a strong power in the West, now less physically involved in Europe as it completes its pivot to the Pacific and to China.

–China and the US, as main rivals this decade, will be share moments of tension and, as all good enemies do, every day will look more alike as centralized technobureaucratic states of surveillance and control. Like true opponents, they will become even more co-dependent, and fear their own dissenters as much as they fear their external enemies.

—NATO, as an institution, will weaken as member states become less and less dependent on it, relying on their own bilateral policies. The divide between the strategic concerns of the Eastern and Southern flanks will deepen.

–European living standards will decrease in most countries (this was an easy one).

–An Intermarium will begin to consolidate in Central and Eastern Europe, led by Poland and backed directly by the UK instead of the US. Poland will act, in a friendly manner, on its territorial ambitions in the Ukraine.

–Related: the Anglo Empire’s representatives in Europe will be not the US but the British from now on. (This opens a potential line of flight for tactical nuclear warfare between the UK and Russia, by the way, but I will not dare make such a prediction).

–Russia, after the necessary changes happen, will become a normalized member in the European political and security establishment. It will become a geopolitically neutered country, like Germany was in the 20th century.

–China will try to agglutinize and support the Spanish-speaking world, as a tool in its conflicts with America.

Outstanding!

In the Outpost we’ll stand facing the dark that lies behind the uncharted lines.