I first came across the @L0m3z Twitter account circa 2016 or 2017 and I was struck by how the things this person wrote in 140 characters were not simply tweets — they were great pieces of standalone writing.

Fast forward to the current year and @L0m3z is one of the kings of anonymous Twitter. He has bylines at American Mind, American Greatness, Galaxy Brain, and IM-1776. His writing is alive and has electricity.

@L0m3z also recently assembled the Passage Prize, a contest that draws upon the untapped talent of the anonymous RW Twittersphere. From the Passage Prize website:

Passage Prize is a monument to the creative talent of the online dissident right and beyond. The book features over 300 pages of short stories, poetry, essays, and original artwork, curated from over 2000 contest submissions. The collection includes all 17 of the Passage Prize award winners plus dozens more outstanding works. The book also includes longform essays from judges Zero HP Lovecraft, Curtis Yarvin, Gio Pennacchietti, and Benjamin Braddock on the meaning and value of dissident culture.

We did a longform Q&A this month via email; I hope you enjoy the exchange.

Q: Congrats on Passage Prize being so well-received. What are your biggest takeaways from the experience, and what does the future of the contest look like? I know you’ve alluded to future editions perhaps including music submissions and childrens’ literature.

A: Thank you very much. I did not know quite what to expect when I began this project, whether anyone would care, or what kind of work we might receive, or even whether or how we would see this thing through to its conclusion (in this case, the book, which can still be purchased at passageprize.com). There has been a lot of figuring things out as we go and many lessons learned in terms of logistics and administration and the hundreds of decisions that need to be made in order to bring a book of this magnitude to life, but my main takeaway is that indeed there is a deep hunger for alternative venues for creative output than what is on offer from legacy institutions. That much, I guess, is obvious and has been for some time. But you really don’t know until you put something out there to test the theory. In that way I regard this first prize as a proof-of-concept for more ambitious culture-focused efforts to come.

We will indeed do the prize again. I plan on announcing the details sometime this summer. I would like to include music (and perhaps children’s literature too) but how these other genres and forms might be integrated into the prize is still an open question.

Q: Mike Elias at Idea Market has written that low-status information and sources should be prioritized in the current environment, and in epistemic warfare, or info wars — whatever we’re calling things now — the ongoing battle is not against lies, necessarily, but the fact that most people don’t want to face the embarrassment of being deceived or being wrong. Along similar lines, changing one’s opinion to align with “the truth” might require allowing yourself to be changed, which can be painful.

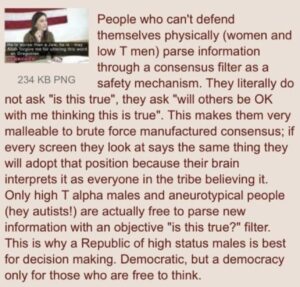

I know you’ve said many similar things, so I was interested in hearing your thoughts on this, and also this 4Chan post, which suggests that certain people don’t look at information and ask themselves “is this true”; they look at information and think “will others be OK with me thinking this is true”?

A: Yes, I think most people do not have the time or capacity to sort out big (or even little) questions on their own. They outsource this work to people in their lives they regard as successful, or properly credentialed, or wise, or who otherwise possess some epistemic authority. This often just means taking on board whatever position prevails within the particular social milieu they find themselves. These are largely rote beliefs. And this is fine. We all do this to some extent. It is a fact of human nature, and I think it is perhaps naive to try to convince most people they should be “thinking for themselves.”

The concern for me is that our totalizing information stream–this kind of digital web we are all now stuck inside of (pardon the mixed metaphors) –– and the way that a particular kind of bugman epistemology flows through that stream and embeds itself pretty much everywhere you look – schools, churches, corporate boardrooms, sports, whatever – produces a single set of prevailing beliefs with no meaningful outside contestation. So what we might do, and amplifying “low-status information” is an example of this, is try to scramble that network as much as possible. Try to disrupt what counts for authority. Break-up key nodes in this reinforcing digital web somehow and return people to more localized, more dispersed kinds of authority.

Q: Randy Weaver passed away recently. For me, Ruby Ridge was key in my understanding of what’s going on in the world today; reading Jon Ronson’s account of it many years ago was a major flashpoint. Do you have a similar incident that has stuck with you over the years and impacted the way you look at current events?

A: I think I’d be giving away too many personal details to tell you exactly the series of events, and my proximity to them, that really shook me up and gave me what might be called a skeptic’s view of received liberal wisdom, but the truth is I have always been something of a contrarian. I can recall a middle-school event about bullying where we spent a week sitting around and listening to lectures and doing exercises where we had to pretend to be disabled or fat or short or have a stutter or whatever and imagine being bullied because of it, and this was meant to teach us empathy and that we were all really the same deep down and the rest of the 90’s era shitlib kumbaya stuff.

I have to say for the record, I wasn’t a bully. I was short and bookish and somewhere in the meaty center of the middle school hierarchy, and also I had and still have genuine sympathies for the underdog – I am not callous to the suffering of the meek – but this whole thing struck me as profoundly false, in every respect. The entire event was an attempt to convince people of an unreality, that merely by “being nice” we might eschew human conflict, like a John Lennon “Imagine” version of social and political life, and I found this to be not only obviously wrong but also intensely harmful since it would blind people to how the world actually worked.

Anyway, I am not sure why this one event remains so salient to me, but that feeling of observing some profound falseness rooted in the denial of human nature is something I still feel today. It is perhaps what is at the root of my beliefs, this intuitive disgust for falseness.

Q: There are two guys whom I think deserve a lot more credit for accurately presaging the current state of cultural affairs in America: Steve Sailer and Jim Goad. Sailer foresaw the trans movement when nobody suspected that would become a thing, and Jim was writing about violent anti-racists in Portland long before antifa became a household word. In your view, who else comes to mind in terms of being adept at recognizing cultural trends before they occur?

I don’t know Jim Goad as well as I should, but I second and third and fourth…Sailer. He epitomizes for me someone who rejects the falseness I describe above. This is why Sailer holds such a special place in my heart. He has always attempted to say what is true without any varnish or concern for reputation. This of course makes him irredeemably evil in the eyes of the regime promoting this falseness, but it is to his unending credit.

I can’t really think of a single other figure who has matched Sailer’s ability to see out into the future, but would point to the collective wisdom of the anonymous right as a decent second choice. And for many of the same reasons. The anonymous right has been correct about so much because of its rejection of falseness and its lack of concern for the liberal pieties that distort so many people’s ability to think clearly about a wide array of topics. But this answer is probably much too self-serving to be persuasive.

Q: In this piece, you wrote:

The Experts at places like the Center for a New American Security, who count as their largest donors Northrup Grumman, Raytheon, Lockheed Martin, Chevron, Exxon, and George Soros’ Open Society Foundation, inveighed to anyone who dare question our continued presence in Afghanistan that this was our duty, our responsibility as free people…The average soldier’s job had been shipped off to China anyway, so at least he could enlist and drone strike an 8-year-old Pashtun boy sent to plant IEDs on a dirt road, and when he got home to the sticks, his psyche fried, he could nod off on opioids until his heart stopped. Our Experts demanded he make that bargain, for his own sake, for the sake of justice in the world. And who was this soldier to object to the Experts?

When I read that passage to my wife — whose Vietnam vet dad is dead; whose brother died of a heroin overdose; whose mom is dead (cancer) — she gasped. To her, the consequences of “America last” policies and foreign wars are not necessarily abstract. In your opinion, do most Americans understand this too, or have they been conditioned (via Russiagate and other methods) to accept the current proxy war with Russia?

A: Unfortunately I think the consequences of America Last are increasingly less abstract to more and more people. And it is not just foreign policy. The same ideology and confluence of interests that put us to war in Afghanistan are also behind the BLM riots and the “grooming” epidemic and promotion of the idea that the antidote to this nationless, de-historicized, deracinated buglife we are meant to adopt is to own nothing and be happy. Except people are not happy. And I think people are beginning to see how this broad complex of foreign and domestic policy all work in concert with one another in opposition to the interests of average Americans. More and more of these puzzle pieces are starting to fit together in the public’s political imagination.

That said, so long as the war with Russia remains a proxy war then I think most people will passively accept our posture toward Putin and his efforts. It’s easy to be sympathetic toward Ukraine given a surface level understanding of what’s going on, and to support their right to independence against what appears to most people to be unjustified aggression. As long as there are no American troops dying there, and no threats to our physical territory, I don’t foresee any significant grassroots efforts to divest us from that conflict.

Q: I’ve been viewing a lot of ’70s films lately — Straight Time, The Gambler (starring James Caan), Blue Collar — plus some ’90s films of a somewhat similar quality — Bringing Out the Dead, Bad Lieutenant. There’s something calming and relatable about these movies as their characters navigate different kinds of hell. Can you recommend some personal favorites similar to these?

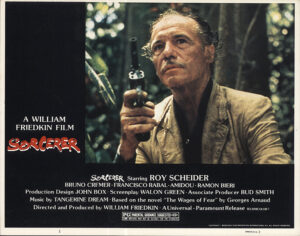

A: First thing that comes to mind is a movie from Mystery Grove‘s film recommendation list called Sorcerer, based on the French movie Wages of Fear which itself is based on a French novel of the same name (I have been trying to get a translation of the novel for a while but so far have failed to–any readers out there know where I can get one?). Sorcerer features the very underrated Roy Scheider of Jaws fame, who alongside a cast of other criminals and fallen men, has to quite literally navigate through his personal hell manifested as an oil patch somewhere in the South American jungle.

I’d also recommend the 1963 film, Hud. This is my favorite Paul Newman movie. It’s based on a minor Larry McMurtry novel that’s also worth checking out. Hud is a less sympathetic character than some of the others in the films you mention above but possessed of a certain inner resolve and hardness in the face of his many problems and fuck-ups that I find compelling. It’s a character that could never be portrayed today, not as a lead, and so is worth watching for that alone.

Lastly, another down-on-his-luck-but-nonetheless-resolute character study that I’d recommend is Robert Duvall‘s Tender Mercies. I love Duvall, and this is maybe my favorite work of his. His character is the opposite of Hud in many ways, in that he’s just overflowing with a kind of warmth as he climbs himself out of the hole. Despite everything, Tender Mercies is a feel good movie at it’s core, though there is a scene where Duvall’s character is briefly reunited with his estranged daughter that still breaks my heart just thinking about it.

Q: I asked Cornelius Stahlblau the following question recently, and I’d like to ask you also: Where do you stand on this Michael Millerman tweet:

“Do you agree with Curtis Yarvin that the American regime can continue in its current state for another 100 years or more, or do you agree with Michael Anton that it is so shaky that even 50 years is optimistic?”

A: I had the privilege of being in attendance to hear Anton and Yarvin debate this very question in person. Their conversation immediately turned to an exchange of esoteric facts about the French Revolution of which only about 50% was intelligible to my smol pea brain. In other words, I could not tell you whether Anton or Yarvin’s arguments prevailed on the merits. I will be diplomatic and simply say that they both made good points.

As for my own hunch, I think Yarvin is right that the US “can” continue in its current state for 100 years, though I am not so convinced that it probably will. Instead, while the branding may all stay the same – the US will still be referred to as such, with its flag and Constitution, however diluted, still intact – I do anticipate a soft kind of regime change that may look in scope something like the regime change precipitated by FDR or the Civil Rights regime that followed in the ’60s. What I mean is that the center of gravity for American political power will be repositioned via some big event that will reshape the country yet again. Whether this is for the good or for the bad remains to be seen. It is important to remember that things can always get worse.

Q: Finally, here’s one more tweet I’d like your reaction to:

The beauty of Alex Jones is that he’s transcended the boilerplate culture war surface politics all these dumb journalists engage in and taken on something holistically spiritual and technological (demonology, systems). He stands alone, he’s like the new Heidegger.

— Contain2 (@textile_ranch) September 30, 2021

A: As you know I am a huge fan of Alex Jones. I think he is one of the great “characters” of our era, a quintessentially American type. I think this tweet is basically right, though I don’t know if Heidegger is exactly the guy I’d compare him to. Jones is doing something far more profound than mere philosophy. He’s constructing an entire cosmos, like a great novelist, like Herbert or Tolkien, that weaves all the main stems of American folk tradition, especially our unique obsession with conspiracism, this deep strain of populist folk epistemology, and bringing these things all into the present to interact with day-to-day politics. And maybe most importantly, he is funny. He is always right on the edge of revealing that the whole thing is a big performative joke, but somehow manages to keep that concealed so that you’re never quite sure where the character ends and the real man begins, or whether there is really any distinction there at all. He is such a fascinating guy. A true national treasure.